"

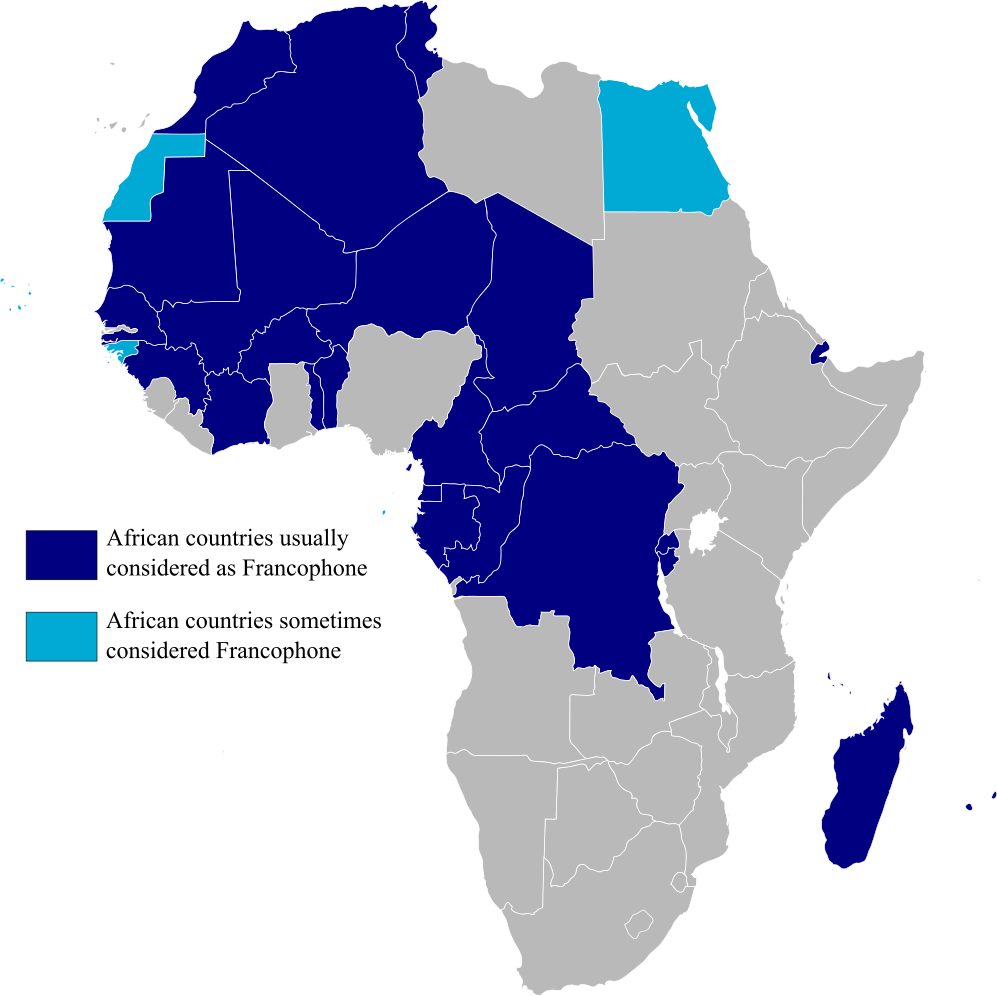

Wolof is THE language of Senegal, and one of six national languages in Senegal given official recognition by the Government (together with Jola, Manding, Pulaar, Sereer and Soninke). Close to 90% of the population of 9 million of Senegal understand Wolof, whereas only 20% of men and 2% of women currently speak French, even though Senegal is officially a Francophone country."

While reading Xala, one topic presented in the novel stood out to me because of my interest in language. The conflict between Wolof and French was interesting to me because it is one of the first times we have read about the difficulties of language in a novel and not just in the articles.

I got this book from the library and while pulling it from the shelf, I saw many other copies of this novel, but published in French, which is it's original language. Even after seeing this and seeing the "translated from the French by..." on the cover page, I forgot that this book was not originally written in English and it caught me by surprise the first few times I saw the difference in languages noted in the story. For example, when El Hadji picks up his two wives for his wedding, when he goes to Oumi N'Doye's house, the text says "..she said in French." I had to stop and think for a moment, "well... what have they been speaking, then?" Obviously Wolof. There are also several other instances that are marked in the text that tell that the characters have been speaking in Wolof instead of French. Another example where language creates a conflict is when N'Gone, the third wife, speaks in French and Yay Bineta, the Bayden, responds, "brindling, 'I don't understand that jargon.' "

Because of the conflicts the French and Wolof usages create, I am curious as to what else the French left behind. Oumi N'Doye brags about having meat imported from France because "native butchers just don't know how to cut," and we discussed in class the French styles Oumi N'Doye loves and the episode between Rama and the policeman. Apparantly

Senegal's currency was created to be linked rate to the French franc; and the Senegal government only owns 41% of the company that regulates transmission of energy in it's own country, while Canada and France own 34%.

The always-informative Wikipedia has a lot of interesting facts about Wolof, and one thing that is extremely interesting to me is that Wolof apparantly does not have any verb tenses; rather, verbs are unchangeable and pronouns denote different times, but there is only one pronoun for all articles, not different ones for masculine or feminine nouns. In case you can't tell, I am very interested in the French language and very glad to know enough of it to converse with someone (as long as it's a pretty simple subject... don't ask me any questions about physics), and it looks like Wolof differs from French so much. French verbs have so many different uses for their verbs - in my dictionary of French verb conjugations, each verb has it's own page and their are fifteen different forms that a verb can be conjugated in. Also, it is very important to know whether a noun in French is masculine or feminine because prepositions can be combined with articles.

If I had more free time (...or any... at all... ever.), this is one book that would be very interesting to try to read in French, because I feel like this is one book especially where nuances of the language would not translate very well. And that's assuming I would even be able to pick up on things like that... but truthfully, I probably wouldn't.

Ahmadou Kourouma- he wrote a novel called The Suns of Independence that has earned reviews in Europe as a masterpiece, but is largely unknown outside Europe and Africa.

Ahmadou Kourouma- he wrote a novel called The Suns of Independence that has earned reviews in Europe as a masterpiece, but is largely unknown outside Europe and Africa. Tanella Boni- she writes poems, novels, essays, and plays, and is very involved in philosophy prgrams and humanitarian efforts.

Tanella Boni- she writes poems, novels, essays, and plays, and is very involved in philosophy prgrams and humanitarian efforts. Marie-Charlotte Mbarga Kouma- she is a playwright, actor, and dancer.

Marie-Charlotte Mbarga Kouma- she is a playwright, actor, and dancer. Yolande Mukagasana- she survived the 1994 Rwanda genocide and published 3 books to raise awareness and in memory of the events.

Yolande Mukagasana- she survived the 1994 Rwanda genocide and published 3 books to raise awareness and in memory of the events.

... And what it became.

... And what it became.